Summer at UW–Madison’s Trout Lake Station means science (mostly)

For 100 years, freshwater scientists from around the world have used the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Trout Lake Station as a home base while toiling in, on and around the lakes of northern Wisconsin. But to the outside observer, the toughest part of summer field work at Trout Lake Station just might be making it look like … work.

“It is crazy that we get to work in this environment,” says Quinn Smith, a UW–Madison graduate student studying walleye, one of the state’s most iconic sportfish. “We’re so lucky to have this place.”

Smith’s arms are stretched wide over the deepest part of undeveloped Escanaba Lake, where he and Jack Abel, a University of Minnesota undergrad, have just finished their weekly data collection of lake conditions like temperature and water clarity.

A curious, red-eyed loon has been quietly shadowing their boat, the Micropterus. Purple spikes of blooming pickerelweed wave in the breeze near the boat launch. Clouds pass one by one across the sun, turning the lake’s surface from blue to green and back. Three or four fishing boats ply the edges of the lake. In such an idyllic setting, you could mistake this research for recreation.

“Well, in some cases, I do literally get paid to fish,” says Abel of his work.

Later, the pair of student researchers don about 60 pounds of scuba gear each and try to look not entirely uncool as they heave over the side of Micropterus to perform what amounts to underwater window-washing. Stretched along the lake bottom — if you can find them in the murk — are an array of sensors keeping constant tabs on the amount of dissolved oxygen available to Escanaba Lake’s various living things.

“There’s always algae growing on the surface of the sensors, and the algae absorbs CO2 and releases oxygen. That could really mess with our data,” says Smith, holding a torpedo-shaped sensor in one hand and a tiny scrap of cloth in the other. “So, we’re down there every week with a little piece of towel or sponge, carefully wiping these sensors clean to make sure we’re getting good data.

“This is what science looks like, sometimes,” he shrugs. “Except we can barely see anything down there.”

As petite as the cleaning cloth and sensor window may be, the scientific research happening at Trout Lake Station is no small thing.

Once and future studies

The data collected for this July week in 2024 by Smith and Abel will feed into decades of measurements from Escanaba Lake, where a Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources research station has been logging the vital stats on every fish caught for nearly 80 years. The crew of Micropterus will use the data in their walleye study, called “Bright Spots,” to describe what makes hardy populations of the fish maintain their strong numbers while other lakes’ walleye counts decline as water warms and other conditions stray from the iconic fish’s preferences.

“Knowing that we can look back that far and find comparable data taken with the same methods in the same places in the same lakes adds so much to what Jack and I are able to do in our own projects,” Smith says. “At the same time, we’re out here today contributing to other projects that people haven’t even thought of yet.”

Catch (and record) and release

Less than five miles away as the bald eagle flies, UW–Madison research specialists Paul Schramm and Carol Warden are contributing to the same kind of partnership on Trout Lake proper, just down the shore from the research station’s own dock. The two have been working together surveying fish and aquatic plants since 2012. The familiarity shows as they pull a sampling setup called a fyke net from the lake. The fyke net is a trap set maybe 30 feet from the lake edge, with a barrier that runs perpendicular to the shore to steer circulating fish into the trap.

With assembly-line efficiency, Schramm and Warden toss the stuff they don’t want — mostly leaves, sticks and ornery crayfish — back into Trout Lake and set to recording the species, length and weight of each fish before releasing them, too, back into the water. Today, Trout Lake gives up chubby rock bass, perch, tiny-but-flashy mimic shiners that barely tip the scale at 1 gram, pumpkinseed sunfish, smallmouth bass and one smooth-skinned and mustachioed black bullhead.

“Once a year we do this on Trout Lake,” Warden says while taking a pair of scales from the back of a fish to archive in the collection at UW–Madison’s Zoological Museum.

Northwoods research for the global good

For more than 40 years, Trout Lake and six other lakes within a short, trailered-boat drive of each other have served as the North Temperate Lakes site of the National Science Foundation’s Long-Term Ecological Research Network.

Across the United States, LTER ties together decades of observations and research at 27 sites representing a broad range of ecosystems — from coral reefs to desert to the Arctic to urban neighborhoods and, of course, the lakes of Wisconsin’s Northwoods. The nationwide network is a resource for an equally broad range of environmental science that illuminates the intricacies of life around us and informs decisions on restoration, recreation, development and more from the local level up to global policy-making.

“Our data gets used by people all over the world,” Schramm says. “Not everyone can get here, but what’s going on in these lakes can still be represented in their work.”

Reestablishing a once staple food crop

On another LTER lake across the highway, Allequash Lake, UW–Madison undergrads Eliana Cook and Marin Danz slog through thick yellow- and white-flowered lily pads. They paddle a canoe to spots where their research team has been planting wild rice, called manoomin in the Ojibwe language.

Danz plops a quadrat — a half-meter square made of PVC pipes — into the water around a single rice shoot and begins recording the water depth and amount of floating and submersed vegetation within the boundary. There’s not much to say about the lone rice plant, which looks like it was snipped off cleanly about 10 inches above the water.

“There’s a lot of signs of herbivory everywhere,” Danz tells Susan Knight, a UW–Madison scientist emerita and former Trout Lake Station director who has arrived in a johnboat. The likely culprits, a pair of trumpeter swans and their brood, glide innocently through the water across the lake, browsing for their lunch.

Allequash Lake was once home to huge rice beds, according to Knight and research collaborator Gretchen Gerrish, who is now director of Trout Lake Station.

“I think it started for me right here on this lake,” Knight says, after pausing to describe the science underway to an interested kayaker and a family headed out to fish — a regular, informal bit of outreach for Trout Lake researchers. “I was here because Allequash Lake has got almost every aquatic plant in Wisconsin, but I could see the rice decline and decline year after year until it was just gone. It’s kind of a mystery why.”

The wild rice research group, supported by the Wisconsin DNR and working in partnership with the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, chose study lakes with community input and expertise from the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, the North Lakeland Discovery Center and lake management consulting firm Onterra. They are trying to unravel the mystery of disappearing manoomin and help rebuild what was once a staple food crop.

Replanting in recent years hasn’t helped Allequash’s historical rice beds much. The lily pads dominate, especially in shallow mud flats. While on the lake, Knight pulls from the water a big lily pad rhizome, an arm-sized, horizontal sort of root from which the floating pads sprout. Here and there, mats of uprooted rhizomes float across the surface of the water.

“We think that while these rhizomes grow from one end and rot from the other, that rotting process fills the mud bed with methane gas and carbon dioxide,” Gerrish says. “That concentrated gas might be what’s ripping up the bottom, keeping the rice plants from getting established.”

An unmatched setting, and sense of community

In September, Trout Lake Station will host a wild rice event expected to draw attendees from many tribes and communities to share cultural and scientific practices and knowledge.

“We’re studying aquatic plant communities, trying to work out all the different reasons why you don’t see as much rice on one lake or another,” Gerrish says. “But the local, cultural impact and partnerships are an example of the extra aspects you get at a unique field station like Trout Lake.”

Trout Lake has its own culture, stretching back to its founding in the 1920s by limnology pioneers like E.A. Birge and Chancey Juday.

Many of the students that seasonally fill out the station’s staff of about 40 (not to mention visiting scientists from many other universities) live on site in a gaggle of buildings originally built on the opposite side of the lake. They were hauled across winter ice on skis when the university acquired the property on the southern shore.

There are touches of summer camp. There’s a raft to swim to, Smith’s weekly homemade pizza night and a fire pit down by the dock that stays busy in the evenings.

“Students want to come back year after year, and researchers from all over will visit and return for new research projects over and over,” says Jake Vander Zanden, director of UW–Madison’s Center for Limnology, professor of integrative biology and advisor to the walleye project researchers. “That’s not just because it’s such an incredible resource in this setting — which it is, just unmatched. There’s also a great sense of community and history here.”

A connected future

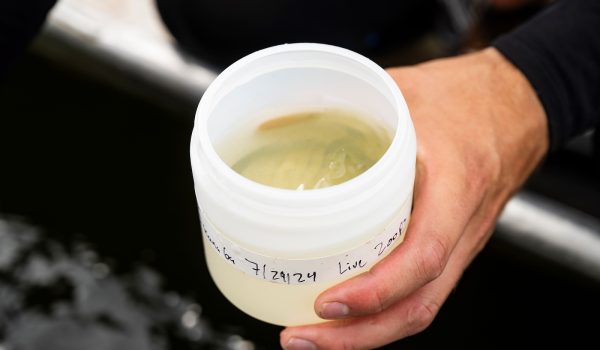

But there’s also a ticking clock as summer days already begin drawing shorter. Students are busy wrapping up field work on projects ranging from the daily migration of tiny zooplankton up and down in the water column to the dietary habits of mudpuppies to an app that offers virtual visits to the lakes.

“People stay busy. They show up in the morning for a staggered start, and by 9 o’clock, pretty much everyone has been in and is out to lakes for the day. Unless they’re sleeping in because they’ve got night work planned.” says Amber Mrnak, station and outreach coordinator, herself preoccupied with planning for the open house, which can draw hundreds of locals and vacationers curious about Trout Lake’s work.

The station is growing. A building under construction will serve as a winter workshop with a makerspace and more room for staff to teach clinics on water quality sensors — events that help community organizations like lake associations understand the benefits of building and deploying their own, relatively inexpensive equipment for monitoring their neighborhood waters. Ideally, those sensors could also be tied into LTER’s network, adding to its reach and pool of data.

Not that the buoys would replace any scientists, who just keep coming back for another field season within a few miles of Trout Lake.

“When I’m at the station, I’m either in the field, at work, making food or asleep,” Smith says. “But it’s hard to think of a better place to be.”