Smartphone technology could combat workplace injuries

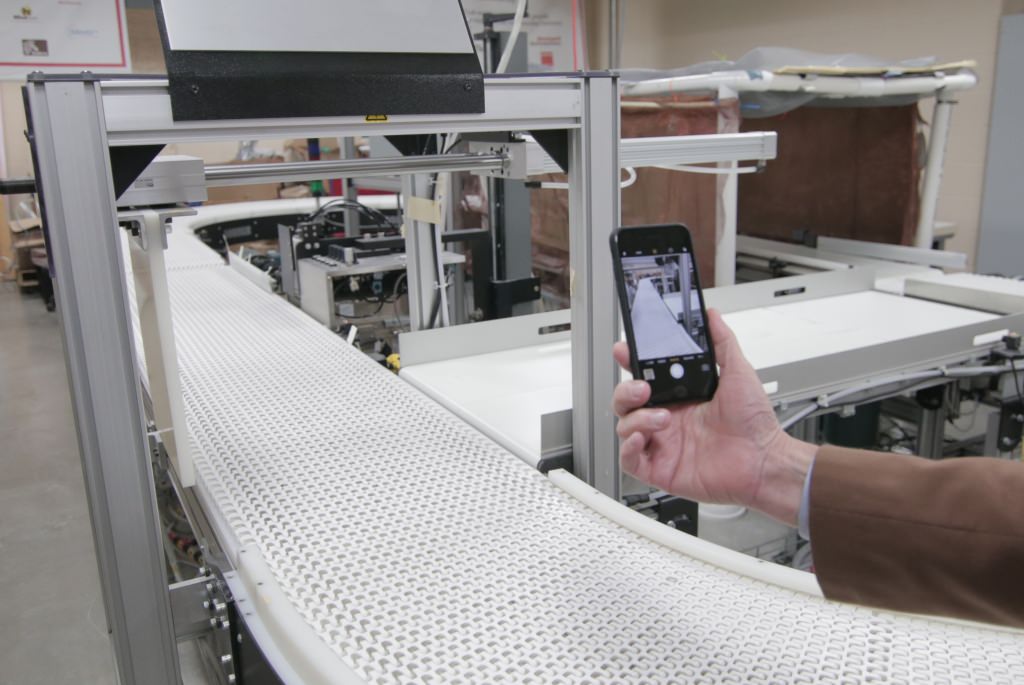

Rob Radwin positions a smartphone to record video of a conveyor belt — a better method, he says, for measuring the risk presented by repetitive workplace tasks and safeguard workers against injury. Stephanie Precourt

Manufacturing industries rely on the efforts of factory employees who work daily to make, package, prepare and deliver the products we find on our shelves.

That’s a lot of physical effort, and the strain can lead to various injuries, such as carpal tunnel syndrome or tendonitis in the wrists, arms and shoulders. Risk of injury is hard on workers, and can create costs to employers for workers’ compensation, lost time and reduced productivity.

“We want to solve these problems before people get hurt,” says Rob Radwin, a University of Wisconsin–Madison professor of industrial systems engineering.

Radwin has been studying this problem for more than two decades, and he may be able to harness relatively simple technological tools such as smartphones to create a solution that is easy, efficient and economically viable.

In the most popular methods for measuring injury risk, health and safety professionals make subjective judgments based on a scale of hand activity. Although these measurements often provide reasonable predictions, there is plenty of room for error in human observation. And judging and analyzing individual work roles and tasks requires valuable time, expertise and training in ergonomics and safety. The work also requires following the nuanced actions of many individuals over a long period of time.

Current technology may speed up and standardize the process.

Radwin and his students — in collaboration with Yu Hen Hu, a UW–Madison professor of electrical and computer engineering — have developed computer vision algorithms to calculate hand activity level.

Support from the National Institutes of Health and a new $1.4 million grant from the Centers for Disease Control’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health will allow the researchers to use videos collected from universities, NIOSH and the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries to develop an entirely new measure for assessing health outcomes.

They plan to use the video footage to track repetitive motion, training computers to recognize patterns of hand movement required to perform repetitive movements, grasping and exerting force. By combining their hand activity measurements with the computerized ability to spot movement patterns, they can create a new, more objective basis for measuring injury risk — knowledge that could help redesign jobs and make the workplace safer.

“We want to solve these problems before people get hurt.”

The goal is to not only to sharpen risk assessment, but to enable companies to produce their own assessments via computer vision. This is where smartphones come in.

“I envision an app, and I think all the technology we need exists on my smartphone today: a high-definition camera, a high-speed processor, and the ability to do cloud computing,” Radwin says.

If Radwin can apply his measures to a smartphone application, manufacturing employers could assess risk of injury of their employees with relative ease and in their own workspace by shooting some video with a handheld camera.

“We can program phones to measure motions and quantify them in a way that is not only more accurate than the current method, but also automatic and more objective and reliable,” he says. “It’s not just for big corporations using ergonomics to cut costs. It would allow medium-sized and small businesses to access this technology as well.”

“All the technology we need exists on my smartphone today: a high-definition camera, a high-speed processor, and the ability to do cloud computing.”

Radwin hopes to help companies make often simple but impactful changes to high risk jobs. For example, if a worker is struggling to keep up with a conveyor belt — and risking injury moving fast enough to risk injury or compromise safety — the new measurement system could help pinpoint hazards, and identify ways to engineer safer tasks. Sometimes problems like these require relatively minor fixes, such as limiting the distances that a worker has to move objects so they won’t be forced to move too quickly.

“Sometimes it’s not obvious until you try and break down the task into its components,” Radwin says.

However, by looking at existing videos of worker motions, Radwin can use the same concept to ensure that these problems don’t arise in the first place.

“Now we can understand how to look at various factors in a job, and try to engineer out hazards before individuals are even involved. That’s our goal, and the goal of companies today: to do it right the first time.”

Tags: engineering, health, manufacturing, research