Eighty years and thousands of stories endure in Classical Myth course

Each spring, for 30 years, classics professor Barry Powell led nearly 500 UW–Madison students in Classical Myth, considered a backbone course for the humanities on campus. So his views on the topic might surprise some former students.

“We don’t want to ‘convert’ [the students]. But while they’re here at UW, we can get them involved and bring them into the oldest humanities tradition. I hope that makes them better scientists, giving them a broader view of humanity and what it means to be a person — in the ancient world and in the modern world.”

Jeff Beneker, assistant professor of classics

“There’s no such thing as classical myth,” says Powell. “It really doesn’t exist.”

Unlike Judeo-Christian scriptures, the nebulous canon of Greek (and, later, Roman) myth represents contradictory stories with varied ages and origins. To Powell, the course simply represents a selection of material and a way of presenting it.

During the last 80 years, however, the course and its leaders have left an indelible mark on UW–Madison and universities around the world.

In Powell’s words, from his best-selling textbook: “Only when we see how myth changes over time, yet somehow remains the same, can we grasp its essence.”

Name a large lecture space on campus — Ag Hall, even the Stock Pavilion — and chances are that the course once met there. Though the loss of one teaching assistant reduced the available discussion sections to a mere 15, the department added a summer session to meet the still-heavy demand.

On a Tuesday morning, assistant professor Jeff Beneker stands in front of the lecture screen on Bascom Hall’s second floor. Only a few of the 478 seats — wooden chairs covered with decades of seat-back graffiti — remain, mostly mid-row; students line the back wall.

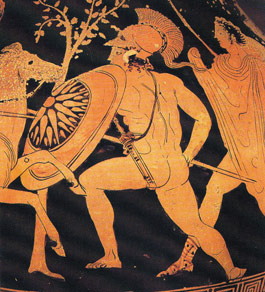

At 9:55, the lights dim. The first lines of Hesiod’s “Theogony,” or genealogy of the gods, appear.

“It’s an instructional text, providing important information when we’re trying to learn how the gods are related,” says Beneker. “But as students of Greek culture, we’re also interested in the literary aspects of the poem.”

With its classical trim and raised stage, the room suits both the topic and Beneker’s performance. The Greek names come alive as he turns unfamiliar words into familiar sounds. Instead of using a pointer, he reaches toward the illuminated text for emphasis, as if grasping each word one at a time.

In 15 minutes, Beneker touches on Greek language, literature, history, geography, spirituality, performance practice, linguistics, criticism and philosophy. No wonder: His syllabus covers a period of more than 1,300 years, forming the roots of Western civilization.

Like most of his students, Beneker didn’t intend to be a classicist. Recalling his days as an engineering student, he can relate to students with packed schedules and little exposure to the humanities.

“We don’t want to ‘convert’ them,” he says. “But while they’re here at UW, we can get them involved and bring them into the oldest humanities tradition. I hope that makes them better scientists, giving them a broader view of humanity and what it means to be a person — in the ancient world and in the modern world.”

“The ancient Greeks invented these stories as a reflection of themselves and their society,” adds associate professor William Aylward, who teaches the class every other spring. “They mean so much to different people. They continue to be popular; they continue to resound. Other topics don’t have this enduring value. That’s what makes it so fun to teach.”

Students agree. Some take the course to satisfy a literature requirement; others enjoy the humorous, often bawdy stories. Tales of heroes, war, sex and scandals elicit just as much interest today as they did in the ancient world.

“It doesn’t take a lot for me to draw students into the stories,” says Jeannie Nguyen, a graduate student who has twice served as Beneker’s teaching assistant. “I think it’s because they’re presented as stories, not facts, open for their own interpretation and opinions on it. Everybody likes to give their own opinions.”

Remarkably, both the material and the presentation of Classical Myth, or Classics 370, still resemble the course’s first incarnation in many ways. Mirroring the transmission of the myths themselves, the lectures and teaching techniques have passed from professor to professor in a true oral tradition.

Walter “Ray” Agard arrived on campus alongside Alexander Meiklejohn in 1927. Agard began in Meiklejohn’s Experimental College before focusing on the classics.

In the 1930s, the department consisted of Latin, Greek and Sanskrit professors, accustomed to teaching literature in its original language. Building on the Great Books studies then in vogue, Agard’s course on myth in translation revolutionized the field.

“Many of my colleagues in other places thought that it was a degradation, practically, to offer courses as superficial as that to people who didn’t study the language at all,” said Agard in a 1972 interview.

At a time when public outreach was considered scholarly research, Agard’s work reached a popular audience of thousands.

“He’s a pivotal figure, making the transition from just teaching Greek and Latin to teaching the classics in translation and getting it out to the public,” says Laura McClure, professor and chair of classics. “It was innovative to teach classics without knowing Greek and Latin. It was only in the ‘30s and ‘40s that the idea became widespread. That gave us the foundation to develop these courses here that we still teach today.”

Upon completing his Ph.D. in 1948, Herbert Howe picked up seamlessly from Agard. Powell describes himself as Howe’s understudy, auditing the course several times and using Howe’s own lecture notes before taking over in 1975.

McClure, who taught the class in rotation with Powell during the 1990s, described her experience the same way.

“I was an understudy for the first year,” she says. “I made tapes of Barry giving the lectures; his idea was that I would ‘imbibe’ the Powell technique, just as he imbibed it from Howe.”

The Powell, Howe and Agard techniques reached their apex with Powell’s textbook “Classical Myth.” Nearing its seventh edition, the book combines a variety of ancient texts with expository materials, evocative images and modern perspectives on everything from “Star Wars” to Seamus Heaney.

“Any book or set of readings is just an interface between the content and the students,” says Aylward, who team-taught the course with Powell in 2006. “This particular book is a phenomenon.”

A true departmental collaboration, the book draws most heavily on Howe’s work. Aylward became co-editor after the fourth edition, contributing material on Roman civilization and Troy. Still, Howe’s own translations form the centerpiece.

“He did a great job of translating the Greek and Latin,” says Powell. “They’re very modern, kind of hip. The book really follows Herb’s lectures. It reserves Herb’s lucid and humorous presentation, which is why it’s been such a success.”

When Powell began teaching in the 1970s, few universities offered courses on myth. Thanks to his engaging text, Ohio State now packs 600 students into a lecture hall each trimester. Universities in Australia, New Zealand and even Taiwan have helped make the book one of the best-selling volumes on the ancient world.

In 1972, Agard described the three hallmarks of good teaching: competence and growth in one’s subject, perspective in organizing material and, “most important of all, having and showing enthusiasm for your material and for your students.”

This is the course’s true legacy. In nearly 80 years, only six people have taught the course. When Howe passed away last year at age 98, his obituary noted that he had taught approximately 26,000 students: “more, he believed, than any other faculty member in the history of UW–Madison.”

“The most passionate, enthusiastic, eccentric professors that I know are from the classics department,” says senior Annabelle Merg. “There’s something about the interconnectedness of classical mythology — oral traditions changing and the integration of surrounding cultures — that makes it impossible for the professors to talk in a straight line. The result is this thoroughly entertaining lecture that leaves you stunned and desperate for more.”

“I knew it was time to retire when a student told me, ‘I love this class; I’m crazy about it, and it’s just like my mother said!’” says Powell, with a laugh. “I realized I’d taught a whole generation.”

Tags: humanities, learning